One of the first things you learn in the military is how to deal with the dislocation of expectation.

This can be expecting to be picked up by some form of transport only to be told you’re now yomping (walking with a heavy pack) back to base or expecting to be going home for Christmas and finding out you are off on a deployment in 2 days time (on Christmas eve). This has been Covid-19 for us so far.

We first started talking about our response to Covid-19 on the 6th of March. From here on in it has been an absolute flurry of activity with various work streams formed. There were heroics and a surge for a solution for something that we didn’t know how hard would hit us. As time went on and with a lot less retrievals than anticipated this turned to over- engineered solutions making things more complicated than needs be and tying ourselves in knots.

Covid-19 tipped us out of a dingy into fast flowing water. After the cold water shock some people were able to front crawl strongly and quickly, some were able to do a slower but more measured breast stroke conserving energy, others were able to doggy paddle not 100% sure how to swim as they’ve never learnt but getting somewhere (maybe not the right direction) but somewhere. Then there were the people from the dinghy that were startled and needing direction and support from those that are already swimming.

Retrievals

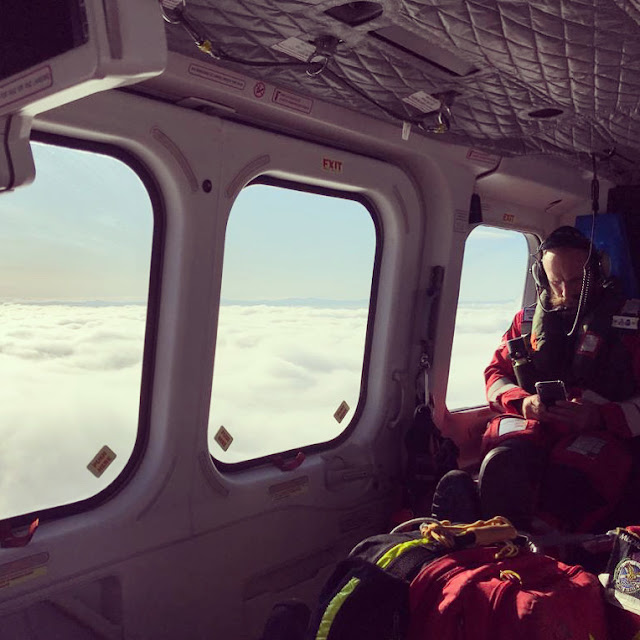

As Specialist Retrieval Practitioner working alongside a Consultant, one of our roles is to bring critically ill or injured patients back from remote and rural sites in Scotland to an Intensive Care Unit within one of the larger hospitals. This is definitely not an easy task and not without risk at the best of times but during Covid-19 things are a lot more challenging as we are constantly working in shades of grey. Like many others we are making difficult and critical decisions based on partial, changing and complex information. The clinical side has been the easier part though, the logistics and transport platforms have been challenging. The amount of extra kit and equipment required and the ability to fly suspected or confirmed Covid-19 patients has been massively restricted. This has led to some mega (I don’t use “mega” in a good way here) road transfers with even the hardiest clinicians a little green around the gills at the other end. We are however learning and developing from each retrieval and sharing experiences within the team. The solutions are beginning to be put into place each and every day with the help of various organisations with can-do attitudes. After weeks of waking up at 3am with thoughts of how to make things work, we are now in a better position and have the ability to retrieve our patients from more far flung locations in a more timely manner.

Pre-hospital Critical Care

As a service we have spent years devising, revising and testing our current systems and standard operating procedures in order to ensure we are at the top of our game and provide the best care to our patients. These are now being thrown into the air and we are having to adapt quickly! Pre-hospital jobs are inherently time critical, sometimes patients need advanced interventions quickly, when you’re trying to get a size 10 boot through a protective suit in a hurry at an emotive scene it certainly takes away that feeling of urgency. In fact, I’m sure you enter into some type of slow motion. This then brings up the question “Are our advanced interventions benefitting the patient when it takes us that extra time to get into PPE?’ Also, are we putting ourselves at extra risk by conducting these advanced invasive procedures? Pre-Covid-19 when we performed bi-lateral thoracostomies we didn’t think that much about the holes we had just cut into someone’s chest. As long as they were kept open and the patient’s lungs were up happy days. What should we do now? Do we seal them? Do we insert a chest drain? Do we need a filter on the chest drain? How much time is this adding to being on scene? and so it goes on. These are just some of the questions we are having to ask ourselves for one pretty common intervention.

We are now making marginal gains in this Covid-19 pre-hospital era we are in. Each job is debriefed thoroughly, systems have been and will continue to be developed, and we will get even slicker. People say it’s not business as usual and in some ways they’re right but I believe it is. We are presented with problems and we are finding solutions to these problems like we always have done.

Like water from a leaky bucket Covid-19 has revealed holes in our service. With something this massive and requiring such huge change in a short period of time I am not surprised. Will we learn immediate lessons? I’m not sure but, I hope as we look into our performance when the dust begins settle we can firstly accept there are problems and look to establish change.

Things I have learnt.

- Do the basics well, I live my life by this and have done since I was a baby Marine. By over complicating something you add unnecessary risk to yourself, your team and patients.

- Be flexible and accept change, in pre-hospital we do this really well on a day to day basis even before Covid-19. Apply this to life and be the first to adapt.

- Leaders don’t always have all the answers, these events are new to them also.

- Realise big events will bring the best and worst out of people.

- Pre-emptive anti emetic is invaluable for road transfers.

- Remain in your circle of influence and out of the circle of concern. Accept that there will be things you have no control over.

- At times you’re not looking for the best possible solution but the best solution possible.

- Remember the dislocation of expectations and be patient.

Great article Wayne. I'd be interested in reading more on your thoughts as a medical professional. Have you got a newsletter I can sign up to?

ReplyDelete